Oceanic currents are the movement of water from one location to another. Since the ocean is always in motion currents are an element of diving. They are easily underestimated which can result in dangerous diving conditions. The best way to prevent emergency situations while diving is to learn how to cope with them and use them to your advantage while underwater.

Currents affect diving in many different ways. Strong currents are difficult to swim against and can cause divers to become fatigued much faster than normal. This also means that divers will use more oxygen faster and reduce dive times. Currents can sometimes be dangerous by dragging divers far from their main locations and away from fellow divers.

What are Currents

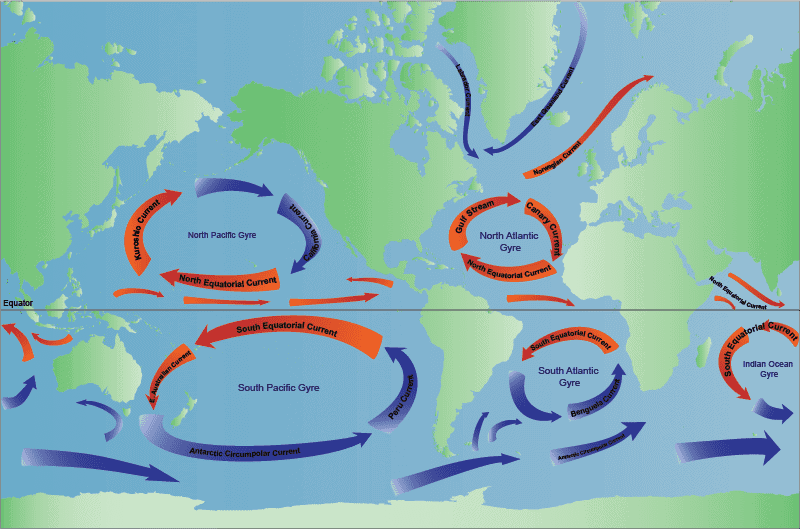

Oceanic currents are horizontal water movements. They are constant but are not always predictable. There are several factors that determine the strength and direction of currents.

To understand how currents affect diving you should know a little about them and how they are created. The three main factors that determine currents are:

Tides: The rise and fall of tides can create currents that are strongest near the shore. These tidal currents are predictable and move in a regular pattern. Tides are controlled by the gravitational attraction to the sun and moon. So the sun and the moon alter the tides which then goes on to alter currents.

Wind: Winds affect currents that are near or at the ocean’s surface. Anytime a coastal area experiences upwelling it is directing due to winds. However, in the open ocean winds can circulate currents thousands of miles. Currents caused by winds move along the bottom of the ocean.

Thermohaline Circulation: Density difference in water due to temperature and salt content create currents through thermohaline circulation. These currents tend to move slower and can occur in both shallow and deep water.

Currents can not only change in strength but they can also change directions. Some areas have currents that completely change directions within a very short period of time.

The majority of currents that divers encounter are caused by thermohaline circulations. Currents caused by density differences from salt content and water temperatures.

How to are currents measured?

Currents are measured in nautical knots. One knot is equal to 1.14 mph. This might seem slow but it’s a whole different story when the ocean is involved. Here are a few examples to put it in perspective.

0.5 knot: If your body is vertical you will be rotated to a horizontal position. It will look like you are a flag flying in the wind.

1 knot: If you turn your head to the side it can become dislodged and your mask can also get flooded.

2 knots: Even a moment of current at this speed and you can get sweep away.

As a general rule, currents at the bottom of the ocean are not as strong as midwater or surface ones. If you are on a dive with strong currents you’ll be instructed to descend and go close to the bottom of the ocean as soon as possible. Objects and formations in the water such as shipwrecks, reefs, caves, or caverns significantly reduce currents and their speed. Keep in mind that currents are not always predictable and some can even change direction during the course of a dive.

Diving with Currents

There are really only two ways of dealing with currents. You can either swim with them or against them. As you might imagine it’s much more productive to swim with them.

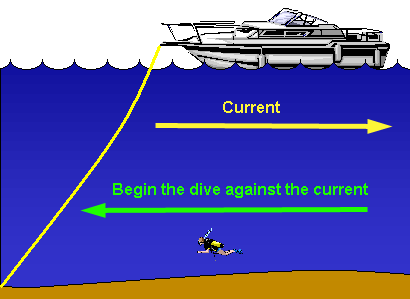

If you are diving in an area that has currents you will probably start the dive swimming against the current and finish the dive by swimming with it. This helps to keep divers safe from fatigue especially at the end of dives.

Another way to dive with currents is to drift dive. This is when you start the dive moving with the current. Allowing it to pull you through a dive site. Instead of ending the dive where it began, it ends farther away. Then, the boat collects the group where they surface.

Drift dives are very fun and there are some intense drift sites around the world. One of the most popular is called The Washing Machine in the Bahamas. Divers are slowly tumbled head over heels through a reef cut. However, drift diving is not for true beginners. It’s best to have at least 6-10 dives of experience before attempting one.

All dive trips start with a debriefing that informs the group about what to expect on the dive as well as safety measures. If there is any kind of current you will be notified about it and how to manage it.

When swimming against the current: This will require more energy and oxygen usage. Keep yourself calm and use your fins and thigh muscles to propel yourself through. To reduce drag, keep your arms and equipment close to your body and streamlined.

If you enter the water with a current the boat will tether a line so that you can descend slowly and with the rest of the group. Always keep both hands on the line and move down by placing one hand beneath the other. This prevents you from being swept away with the current.

When swimming with the current: Always keep your body as relaxed as possible. This will help you float along and stay with the current. If you allow yourself to relax you will also enjoy the ride from the current.

The ascent is much easier. Since you swam against the current going out you will be able to glide with it on the way back. Allow yourself to float back keeping your awareness on the guide line used at the start of the dive. Use this same line to slowly ascend making sure to conduct a safety stop for at least 3 minutes. Use the same method of hand over hand to guide yourself up.

Dangers of Currents

Depending on the current and how strong it is, divers can easily get swept away. One wrong turn of your head in a current can flood your mask and cause panic for beginners.

Swimming against a current can cause fatigue and make diving more difficult. This is why it’s important to understand currents and how to dive with them.

Some of the possible dangers of diving with currents include:

- Flooded mask

- Fatigue

- Rapid air use

- Disorientation

- Swept away

- Rapid ascent (decompression sickness)

Safety Tips

1.) Gear: Always make sure your gear is securely attached to you. Any accessories such as cameras or lights should be connected to your BCD vest. This helps to ensure you don’t lose anything and also that you are not swept away if the current grabs hold of one of these accessories.

2.) Weights: The normal way to weight in strong currents is to go heavier than usual. This helps you descend faster and reduce the risk of being swept away.

However, it’s good to remember that being overweighted makes it harder to neutralize and find buoyancy. Be sure to allow enough time to adapt and adjust to this difference.

3.) Alignment: Once you descend, stay as close to the bottom of the ocean as possible. Make sure not to touch or harm anything at the bottom of the ocean. Such as reef or other ecosystems.

It’s best to keep your body in a straight line. Tuck your arms in and keep them flat against your body. Most divers find it comfortable to keep their arms folded at their chest.

Streamlining the body like this allows for an easy flow with the current and reduces the chance of flooded masks or getting swept away.

Why This is Important

Knowing about currents and how they move helps to ensure safety during dive trips. Educating yourself on the risks will ensure proper responses if the situation ever occurs.

Always inquire about currents at local dive shops if you are diving without a guide. On organized trips, the divemaster will brief you before the dive and inform you if there are currents at the location.

The more dive education you have the more confident you will be in the water. For continued education, PADI offers many courses focused on specialized training for all types of situations and events.